For all the goodbyes she had said in her life, Tory wondered that they never seemed to get any easier. But there was no time for sentiment now. Just before dawn, Cully ran into town to engage a carter from the docks; it were better if the players were not perceived to be breaking camp. Ada Bruce took the opportunity to embrace Jack in farewell. Jack entrusted Captain Billy with his letter of regret for the management of the hotel, and Billy provided him with several cards on which he scribbled notes of introduction to some of his theatrical connections in England.

"Capital business, England for the season," he beamed, as if their departure was an entirely professional decision. "We’ll look you up in London one day, I daresay!"

Edward was still asleep in the caravan when Jack and Tory went in. But Marcus was alert. His face lightened for an instant when he saw Jack, but he hung back from them both, his wide forehead furrowed with unhappiness, his dark eyes accusing. He must know they were leaving, and Tory could not blame him; she had scarcely been any older than Marcus when she'd lost her mama. She hugged him hard in goodbye, then waited by the door, in the shadows. Jack put out a hand toward the boy, where he sat on the edge of a little trundle cot, but when Marcus shrugged the gesture off, Jack crouched down beside him instead.

Marcus’ eyes flicked sideways at him. "Me know why you come."

Jack drew a breath. "I’m here to thank you. You did a man’s job last night. Tory told me all about it. You saved Alphonse’s life. You’ve made us all very proud."

"But you still going away."

"Not because I want to. Not because of anything you’ve done. You don’t think I would leave you if I didn’t have to?"

The child shrugged up his small shoulders, gazing at the floor.

"Marcus?" Jack pleaded.

"No." His small face tilted reluctantly toward Jack’s. "But me no want you to go."

"I don’t want to go either, not like this. But Alphonse needs our help. He isn’t safe here. We have to take him away." Jack made an effort to master his feelings and hurried on. "And now Cybele needs your help. She’ll depend on you more than ever."

"Me no play no more wit’out you," said Marcus.

"Of course you will. You have a very special gift, don’t you know that?" The child eyed him warily. "We’re leaving you your Pierrot costume and most of the props. They should last awhile, if you take care of them. And pretty soon, it will be time for you to teach Edward the trade."

"Edward!" Marcus hooted, in spite of himself. "Him too clumsy!"

"He’ll outgrow it, just like you did. You just have to be patient. You’ll make twice the profit," Jack pointed out.

Marcus cast a doubtful glance over at the smaller boy, then shrugged again. "When you come back?"

Jack’s eyes fell; he looked as if he’d been punched. "I...don’t know."

"Nevah," said Marcus, wistfully.

"Maybe not," Jack murmured.

"You fo’get all 'bout me."

"Never."

Jack reached for him, and this time Marcus did not resist. Then Jack was straightening up, hugging the boy to his chest, unable to say any more. For a moment all of the child’s dark limbs were tightly wrapped around Jack, and his face was hidden in Jack’s neck.

"I’m going to miss you so much," Jack breathed against Marcus' curly hair.

"Me too," sniffed the boy. "Me wish you no have to go."

"Me too."

Then Marcus sat up with sudden resolution in Jack’s arms, and Jack set him back on his bed. The child was done with crying. He only watched wide-eyed as Jack turned and hurried past Tory to leap out of the caravan. She followed him outside, found him standing in the dark, staring at the ground.

"Cybele will take good care of him," she told him.

Jack nodded slowly. "I just wish...I had more to give him."

"You’ve given him a piece of your heart," Tory whispered. "And he’s smart enough to know it. There’s nothing more you can do."

Jack shook his head miserably. "It’s not enough."

Cybele came out of the wagon and glided up to them, pressing a packet secured with strings into Tory’s hand.

"This all I have left in the wagon. Can you find such things in England? I do not know. I write out the receipts, but I only know the French name for some things. Alphonse must translate."

Tory could not respond before she was enfolded in Cybele’s thick, strong arms. "I hate to leave you," Tory whispered.

"Your destiny lies another way from mine, cherie, away from these islands. But I have something for your journey." Cybele stood back and dug out of her apron pocket a fistful of pungent, papery dried herbs and crushed flowers. She sprinkled some over Tory’s hair and kissed her cheek, then turned to anoint and kiss Jack the same way. Then she took both of them by the hand.

"The Great Mother in all her many names protect you both, wherever you go." Cybele joined Tory’s hand to Jack’s. "Love a more blessed thing than gold, and more rare. As long as you care for each other, the Great Mother keep you from harm."

Tory felt light-headed, she was so near to crying, but Jack looked very sober. He drew her to him, right in front of Cybele, and kissed her deeply, then held onto her a moment longer. Tory burrowed into his embrace, delirious and embarrassed, salt tears leaking down her cheeks.

"Thank you," she heard Jack whisper to Cybele, but she was far beyond words by now. She could only hold him tighter.

Cybele, however, was once again her old pragmatic self. "I put some food in your pack. It be a long journey, and you must eat."

Jack nodded. "We’ve taken our costumes and some day clothing and a few props that we can carry. And two blankets. Everything left in the wagon, that’s for you and Calypso and the boys. Sell whatever you can’t use. The wagon and the horses are yours."

"But no! You be too generous to me already, you and Alphonse. You put all your profits into that wagon. I cannot accept."

"We can’t very well drive it across the Atlantic."

"Then I pay you—"

"No, Cybele, you've done so much for us, and you’ve a family to raise," Jack declared. "We have enough for our passage and a little left over for our landing. We’ll be all right."

Alphonse emerged from the shadows, folding a paper, which he handed to Cybele. "Take this document to Mr. Jepson when the season here is over. I have noted the address. He will be expecting you." Cybele nodded and secured the paper deep within her bodice.

"The wagon must remain here after we are gone," Alphonse hurried on. "If the militia comes back...when the militia comes back—"

But Cybele waved off his advice, whatever it might have been. "I deal with foolish men all my life."

Jack would have preferred any other conveyance than a troop ship. But a low-rated frigate, carrying its weary crew home from a tour of the Indies, was the only vessel leaving for England when they finally arrived at English Harbour. Her captain had seen Jack and Tory perform at one of the Commissioner’s dinners, and was glad enough to earn three fares of passage on his own account. Far from the aborted plot on Nevis, they were simply players sailing home to try their fortunes in England. When the formalities were concluded, each of them signed the manifest. Miss Victoria Lightfoot. Mr. Alphonse Belair. Mr. Jack Dance.

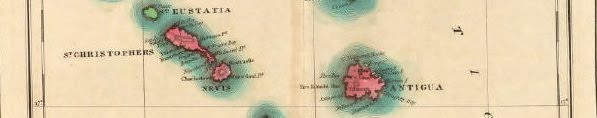

They had spent a day in the back of an oxcart, jouncing along the Round Road out of Charlestown for the windward coast. This was followed by a night in a creaky little sloop Alphonse had signaled, after dark from a hidden cove, that carried them to Falmouth Harbour on Antigua. He had thought to engage the sloop for two nights running, he told them, in case there were any strays from Gingerland. He never expected that he would be one of them.

"At least you know your money was well-spent," said Jack.

"But it is a very cruel kind of justice that I should escape when so many others must stay and bear their misery," Alphonse sighed.

It was no less cruel, Tory supposed, that Alphonse should find himself facing an Atlantic crossing when he had yet to recover from his night in the sloop. Efficient parties of sailors were racing to man the braces and sheets, and swarming up the shrouds into the rigging to make sail, when she spied Alphonse gripping the rail nearby with both hands. He was frowning out at the grey water under a cloudy sky, as the ship began to lurch and shiver under sail.

"I hope this won’t be a mistake," sighed Jack, standing beside her amidships.

Tory turned to look at him. "Surely even Alphonse won’t be ill for the entire voyage?"

"I meant...everything. It seems like every time we try to make a fresh start, it all blows up in our faces."

"But we can’t stop trying. We'll make it all up anew, as we always have. Like a play."

Jack shook his head. "But what about you, Rusty? England isn’t your home."

"My home," echoed Tory. "Well, had I stayed in my home, I suppose I might have become an underpaid governess by now. Or some grey-faced matron wed to a...a greengrocer’s apprentice at sixteen, who wakes up after thirty years have slipped by to wonder what’s become of her life. Instead of—"

"A rootless vagabond in a tattered pantomime adrift in the middle of the Atlantic?" Jack suggested.

"A life I choose. With the man I love," she corrected him. "I’d do it all again."

Alphonse was coming toward them with careful steps, even though there was not yet much of a pitch to the deck.

"I go below now to die in peace," he announced.

"We’re not out of port yet, Alphonse," said Jack.

"If you let these English cast my bones into this accursed sea, my miserable jumby come back to hound you round the world for all eternity."

They watched as he lowered himself down the hatchway with great dignity.

"Will he be all right in England?" Tory asked a moment later.

"Alphonse will do splendidly well. He has more manners and polish than I could ever hope to command."

Jack said nothing more for a few moments. The white of spreading canvas began to blot out the scrubby green landscape of English Harbour, now receding into the background on either side of the frigate. Tory could feel the stirring of power as the sails caught the breeze, and the ship stood for the harbor mouth and the open sea. From every direction, plain, hearty English voices were calling out orderly commands and crisp responses. No trace of island music could be heard in any of the voices, nor was there any idle jesting or laughter among the men. When Jack turned back to look at Tory, his eyes were full of apology.

"Ah, Rusty, it’s an awfully damned civilized place I’m taking you to."

"I’d march into the flames of Hell, so long as we could be together, hombre," she declared. "You know that."

"Aye, we’ll get there soon enough, at the rate we’re going."

Tory smiled and slipped her hand into his behind the cover of her full skirt. Jack’s long fingers were warm and reassuring as they closed around hers. And the frigate bent her sails for England, the destination of all runaways from the Indies.

The End

(Top: Harlequinade Finale, Pollock's Toy Theatre Pantomime Characters, 19th C, as seen on freespace.virgin.net/.../Costumes/Costumes.htm Hand-colored by Lisa Jensen.)