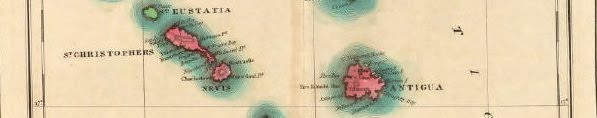

It was a different sort of custom than they had played to last season in Charlestown. Tory noticed it even as she juggled pins in her opening business. The island quality and their grand carriages were entirely absent, off to the ball—or at least, the ladies. There were no able-bodied white men of any station present, so it must be true, what Jack had overheard. They were all turned out for the island militia. They would have made Gingerland by now.

That left an audience of mostly brown and black townsfolk from the free colored communities, tradespeople, laborers and children, a smattering of country servants attached to the ball-goers, and the usual curiosity seekers up from the docks. Tory recognized a bluff, grizzled, one-legged English seadog who called himself Salty, and whose chief occupation was trading stories for drinks in the grog shops. And most were in a jolly humor, eager for diversion. The fate of a few unruly slaves up in the hills was no affair of theirs. Or mine, Tory reminded herself, forcing a smile onto her face.

Marcus had cartwheeled all round the stage in his Pierrot rig. Now he made his first appearance in the Punch costume, juggling hoops. Tory couldn’t take hers eyes off the peculiar slope to one of Mr. Punch’s shoulders where the padding sagged, and the paste mask sat at an odd angle; suppose it slid down over the boy’s eyes, blinding him, or fell off his face altogether? Then Punch tossed her a hoop, and she had to concentrate on the business at hand. Toward the end of their routine, Marcus dropped a hoop and Tory’s heart froze, but he caught it up again so deftly on the first bounce, it was possible no one had noticed. Scarcely remembering to bow to the applause, she hurried Marcus offstage to make way for Captain Billy.

Ada Bruce was halfway through her hornpipe when Tory saw a signal from Cybele in her stall by the road. Peeping out from behind their stage, Tory spotted them too, white faces at the back of the crowd, three or four younger men flanking an older gentleman in the type of brassy frock coat favored by deputized officers of the militia. Were they watching for Alphonse? Did that mean they hadn’t caught him? Or were they lying in wait for Jack?

Tory could not bear to watch when she sent Marcus back onstage for the Punch solo. She busied herself backstage, alert to every murmur and titter from the audience, waiting for the collective groan or gasp that would tell her calamity had befallen the boy. But he came skipping off, exactly on cue. And then it was her turn to fling open the curtain and take the stage as Columbine.

"Poor Harlequin was spying on the moon,

Offending fair Diana’s modesty.

Moonstruck, he’s fallen deep into a swoon,

Insensible to earthly cares, and me."

A limp bit of doggerel, this, but she hadn’t had much time to compose it, and it would have to serve. The audience had been promised a recitation, after all. The waning moon would not be up for hours, but she pitched her words to a strategically placed torch, by whose flickering light the outline of the Harlequin outfit was just visible. It was stuffed with straw in an attitude of sprawling torpor at the back of the stage. A rather mangy cocked hat from Captain Billy’s wardrobe rested atop one crooked sleeve, so the figure would not appear to be headless.

"Without his magic bat to keep me safe,

That rascal, Mr. Punch, will try his odds,"

Tory continued, turning full into the pool of torchlight and stretching her arms imploringly to the audience. Then she set her hands on her hips in a saucy gesture.

"I’ll dance the foolish clown a merry chase

And send this boy to plead before the gods."

Marcus trotted out as Pierrot, and somersaulted to his knees at her feet. Tory pantomimed sending him off on a journey, and the boy leaped up, danced a jubilant figure around her, and cartwheeled off. Tory made herself count slowly—take your time, draw them in, that’s what Jack would say—as she turned again to the spectators, marched downstage, and threw up her arms toward the "moon."

"Oh, Goddess! Listen to my hopeful cries,

Your mortal sister! Do not turn away!

For when the gods to mortals close their eyes

All fellows know the Devil, him make play!"

There were hoots of appreciation in the audience for this bit of island patois, and expectations were high for the devil to come. Tory ran to grab two of Columbine’s kitchen spoons from a pile of utensils in a corner, then ran back to the supine Harlequin, clapping the spoons together over him, and waiting, poised, as if for a response.

Then Punch raced in from the other side of the stage, lost his footing, and lurched into the pile of kitchenware with a crash that made the audience jump, then laugh. Punch righted himself, Tory breathed again, and he grabbed up a ladle and a rolling pin, paused to mime a leer in her direction, and the chase round the stage began.

Between the tumbling and the slapstick, and the breakneck feats, and the exits and entrances, along with Columbine’s periodic cries of "Lo! Harlequin wakes!" to fool Mr. Punch and the audience, Tory lost track of the militiamen in the audience. Once, she heard the hoofbeats of a rider in the road, and relief pumped into her throat so fast, she nearly choked on it. Jack, it must be Jack! But when she stole a look, it was only another man in a military coat, sliding off his mount to talk to his fellows.

Anxiety clung like weights to her limbs and her heart, but Tory pressed on. She didn’t even know what she was doing onstage any more, her business was all rote by now. She only counted the beats until she could finally get off this damned stage and find out what was going on. In another minute, maybe two—

Then she suddenly realized Marcus had missed his cue to return to the stage. Well, it was a lot to ask of the boy, but he’d get there in the end. She pirouetted around the stage a second time, juggling higher, kicking up her skirts. On her third go-round, Punch finally appeared again. He did a handspring, a forward roll and two cartwheels, as if in apology, then dove again for the prop pile, coming up with two spoons and a rusted carving knife. Damn, she'd told him no knives! But he was putting on a hell of a display with it. Tory only hoped his showing off wouldn’t ruin them all. He was chasing her across the stage, to the audible delight of the crowd, when a shout came up from its midst.

"Ho, there! Halt in the name of the Captain-General!"

All four militiamen and both officers were marching through the crowd toward the stage; it was a nightmarish repeat of that day in Basseterre. Tory ran downstage without a backward glance, still clutching her props. Surely Marcus would have sense enough to slip away behind her.

"What, sir, is the pantomime unlawful in Charlestown?" she addressed the officers, broadly, as if she could transform the scene into a part of the play and control it.

"Riot and rebellion are unlawful in Charlestown, Miss," grunted the newly arrived officer of the militia, as he leaped up on the stage. "Stand aside," he commanded her. "I’ll have a look at your little darky there."

Damn, Punch was still lingering upstage. But when Tory moved instinctively to block the officer’s path, and buy an extra second of time, the man shoved her aside and into the grasp of another of the militiamen. who were now swarming across the stage. Scarcely aware of being handled, she was calculating how quickly she might throw off her guard and tumble into the officer before...

But then Punch too was in custody, grabbed from behind by a militiaman who emerged out of the shadows. Tory wrenched herself forward, dragging her guard with her. They must not discover Marcus in Alphonse’s costume, it would look like the ruse it was. What an idiotic idea this was, now they would all be implicated in a slave conspiracy, all of them, and it was her fault. Jack had been a fool to leave it in her hands.

The officer yanked off Punch’s conical hat and tore away his mask. He took one step backward as if from a blow when Alphonse's face, shiny with exertion, tilted up to gaze at him.

"Gentlemen," said Alphonse.

Tory was ready to swoon with relief, but she dared not waste an instant of her advantage.

"Please, sir, be good enough to tell me what the matter is," she exclaimed, half-turning to the curious audience, who were crowding in around the stage.

The officer dragged Alphonse downstage by the shoulder, toward a pool of torchlight, for a better look. But he stopped short of the spot when he noticed the dozens of onlookers’ faces ringing the stage.

"I have information that this fellow is implicated in a rising," he declared. That set the crowd to prattling.

"Where?" Tory demanded, aping surprise. "When?"

"This evening, in Gingerland," the officer responded. "But the conspiracy was discovered in time, and the ringleaders are being dealt with," he added, to the crowd. "No property has been lost. There is nothing to fear."

Dealt with. The words made a sinister pounding in Tory’s head. Where the hell was Jack?

"But Gingerland is miles from here," she protested, in her most innocent and reasonable voice. "And we’ve been playing here since nightfall."

This produced affirmative noises from the crowd.

"Aye, and the little Punch, too!" roared old Salty, drumming his wooden stump upon the ground. "Took after the wench with a roller pin, 'e did. I wanted to see 'ow it all come out!"

"It’s true, sir," muttered the young fellow who still gripped Tory by the shoulders. "They’ve been at it all night. We’ve seen 'em. Him and the lady, and that musical couple. And the lad."

The Bruces had come out from backstage to lend whatever support they could. Marcus stood between them, dressed as Pierrot.

The officer let go of Alphonse, with a huff of impatience.

"Somebody’s eyes are playing tricks," he growled. But he could scarcely dispute the eyewitness account of his own men. "We shall sort out whose in the morning. And you had better make yourself available for further questioning," he told Alphonse. "Who has charge of this enterprise?"

"I do, sir," cried Captain Billy, hurrying forward before Tory could think of any more plausible response. The militia officer sized up Billy Bruce, and seemed to relax a bit.

"I must close you down for tonight, on orders of the Captain-General of the Leewards. Between you and me," he went on, in a much lower voice, "there may be more violence done tonight, before we catch the last of 'em. Best to get all the ladies indoors."

"Capital suggestion, sir. I quite agree," nodded Captain Billy.

It was slow torture for Tory to have to behave as if everything were all right, picking up the props and clearing the stage while the militiamen dispersed the audience from the clearing. Gazing back once toward their campsite, Tory spotted Shadow tethered with the other horses, cropping idly at the green scrub. But she could see no trace of Jack. At last, when the remaining militiamen were standing far off, Tory found Alphonse behind the curtain.

"Are you all right?" she breathed, grasping his hands.

"Yes, yes. I’m sorry—"

"Where’s Jack?"

Alphonse’s dark face furrowed with trouble. "Victoria, I do not know."

"It was never a rising," Alphonse declared, when they were finally alone, and he'd told her how he and Jack had parted. "It was an escape. Since Jack told you the rumor, I owe you at least the truth. But it was never my intention to involve any of you."

"But why?" Tory begged. "After Whitehall? Why?"

Alphonse shifted uncomfortably. "I...owed it. To a friend."

They sat on the floor of the wagon, the lamp very low, the door open to the campsite. Cybele was setting out pallets for those who would keep watch tonight—Captain Billy, Cully, herself. Horsemen passed now and then on the road, and once Tory heard the echo of baying hounds from the mountain. The militia hunting down the last of those who had tried to escape.

"What will happen to them?" she asked uneasily. "The stragglers?"

"Shot, if they run. Sentenced to hang if they are taken. Running off alone is one thing, but if they are caught in a plot—"

"And the others?"

"Most had the sense to return to their cabins. Scores were ready to escape, if it could be done in secret, but less than a dozen chose to fight or run. The rest were able to save their lives. Because of Jack."

Tory closed her eyes against despair. It had been hours.

"He is a white man," Alphonse told her gently. "He will not be shot on sight."

"Unless they mistake his clothing in the dark," she murmured. "Or storm the place he’s being held."

"Paris will let him go before then, he is not a monster. And if the militia captures him, he can claim he was a hostage in a...rising," Aphonse spat out the word. "They will not harm him. But more likely, he has slipped away already."

Tory only nodded at such cold comfort.

"It might have succeeded," Alphonse sighed, almost to himself. "So many of them were determined to go; they had been preparing their hidden escape routes off the mountain for months. After dark, when the masters were all away in town. I had only to provide transport off-island, and safe houses, until they might make their ways to English Harbour to take ship for England."

"England?" Tory echoed. Most runaway were fortunate to get off-island, let alone across the ocean.

"Do you know that a runaway cannot be reclaimed by his master in England?" Alphonse replied. "It is the law. They had only to bide their time in hiding for a few weeks until the shipping lanes reopened and enough shipping came through English Harbour to carry them out of the Leewards. It should have worked."

"Why didn’t it?" Tory asked. "Who would betray them?"

"Jack would not tell Paris, but he told me. A field girl. Venus."

"But, I know this girl." Cybele was standing in the doorway. "Venus. She come see me all the time."

"What for?"

"Why, the same thing you come to me for, cherie. She crave motherhood no more than you, for all that she only a poor slave."

"She has a lover?" Tory asked.

"If that what you call it when a bull put to the cow," Cybele snorted. "Her master lock up the young slave men and women together at night, according to a schedule."

"His great experiment, improving the strain for field work, as he calls it," Alphonse agreed. "It is the worst kept secret in the Leewards."

"But why should Venus betray the others to a master who uses her so?" Tory wondered.

"For freedom." Alphonse's voice was bitter.

"But they might have all escaped—" Tory protested.

"Ah, but escapes often go wrong," said Cybele. "Plots go wrong every day. But the grand blancs so terrified of a rising these days that any slave who betray such a plot to her master almost certain to be freed for it. How else can a dark-skinned girl like Venus gain her freedom without having to bear a child she no want?"

Tory closed her eyes again. How indeed? How could anyone survive in these beautiful and benighted islands?

"Is it safe for you to stay here tonight?" she asked Alphonse.

"If they had any evidence against me besides hearsay, they would have taken me off that stage when they had the chance. For now, I look more guilty if I run away."

He shifted up to his feet when Calypso opened the door of the Bruces’ caravan, where she had put the younger boys to bed. Stepping to the threshold, he paused to look back at Tory.

"There is...one more thing," he told her, his expression grim. "There are many troops of militia all over the mountain tonight. But coming down the trail, I recognized one man in particular. It may come to nothing, their paths may never cross—"

Tory could not have looked any more stricken. Alphonse had to avert his eyes.

"It was Constable Raleigh of Basseterre."

(Top: Columbina, by Tony Banfield, based on the illustrations of William West. As seen on pennyplain.blogspot.com/)