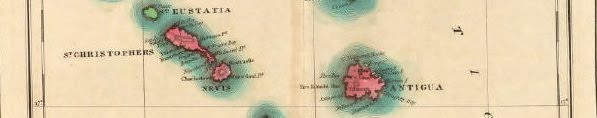

Their first few days alone together back on Nevis reminded Tory of the first carefree months she and Jack had spent in the Leewards, traveling the back roads of St. Kitts, with only the clothes on their backs and little more to worry about than earning their next meal. It was like that now in Charlestown, as Nevis began to shake off the doldrums of the gale season. Anxious to be gone from the military base at Antigua, they had come to Charlestown early —no wagon, no children, no pantomime, no purpose. They would resume their formal playing with the others soon enough, when the season began at the Bath Hotel, but for now, they were simply enjoying themselves, juggling and tumbling on street corners in happy anonymity, playing wherever the spirit took them.

But Tory remembered the folly of happiness on the morning she and Jack came laughing round the corner of a side street and found themselves face to face with Alphonse, walking with a mulatto man with fierce dark eyes in the neat livery of a well-kept house slave. Tory's cry of relief curdled in her throat at Alphonse's taut expression; for a tense instant, it looked as if he might not acknowledge them at all.

Jack and Alphonse locked eyes. No one spoke, but the current of tension between the three of them alerted Alphonse’s companion. Youth was fading from his proud, face, and his gaze slid over Tory like a chill, but his expression turned to ice when he looked at Jack. The mulatto slowed, and his hand rose to the hem of his waistcoat, but Alphonse’s small, dark hand came out to stay his arm.

"It is all right, Paris," Alphonse murmured. Then he turned to give Jack and Tory a brief, civil nod. Jack nodded back, but his hand closed on Tory’s elbow, propelling her on to the end of the street without breaking stride. They did not look behind them again, but Tory could feel the cold eyes of Alphonse’s companion boring into their backs.

"What was that all about?" she breathed, when they had turned the next corner.

"I don’t know. I don’t!" Jack insisted, to her accusing look. "I saw Alphonse speaking to someone in the wood on the morning before he left St. John’s, but it wasn’t this fellow."

"Why didn’t you tell me?"

"Alphonse speaks to strangers all the time, most of 'em slaves. If he had taken me into his confidence about some dangerous business, do you think I would try to hide it from you?" When Tory sighed and shook her head, Jack hurried on. "Well, he’s seen us now. If he wants us to know what he’s up to, he’ll tell us."

But Alphonse was not much more forthcoming when he materialized out of the shadows outside their lodgings that evening.

"You are early for our appointment," he greeted them.

"And we’re so pleased to see you, as well," Tory snapped back, jittery with unease.

"Of course, it is good to find you both well," Alphonse sighed. "I am grateful for your discretion this morning."

"We wouldn’t dream of interfering with a man enjoying his holiday," said Jack.

"I am here at the request of an acquaintance for whom I am doing a small favor. It is not worth speaking of." Alphonse shrugged the matter away. "But why are you not on Antigua?"

"The ships are leaving English Harbour. There’s more trade here," Jack offered. He did not mention Mr. Nash.

"You are performing already?"

"Well, we’ve been larking about the marketplace," said Jack. "The others will be along directly. There'll be nothing to hold the Bruces there, once the officers leave the station, and Marcus will be in a great hurry to rejoin us."

"So it appears our season here has begun." Alphonse sighed again. Tory thought she saw a glint of distress in his carefully composed expression.

"We can look after ourselves if you've business to conclude," said Jack.

"But if we are all in Charlestown, we are expected to perform together," Alphonse reasoned. "It looks odd if we do not."

"To whom?" Jack frowned.

"If we are not to be taken up for vagrants before the season opens at the hotel, we must find some employment."

"We could begin the pantomime when the wagon arrives," Tory suggested.

"No." Alphonse said quickly. "We must leave poor Harlequin in his box for now. But I will join you at the market until the others arrive. We shall need to practice in any event."

He waved a hand toward the tavern where they had their room, beginning to hum now with its usual evening custom. "But first," he went on, with a show of heartiness. "I shall buy us a bottle of wine, and you may tell me your plans for the Bath Hotel."

When the others arrived, Jack decided to set up their stage at their old campsite off the road to the hotel. He had worked up some lively verbal duets from Richard III and A Midsummer Night’s Dream to add to their scenes from Hamlet, Macbeth and Twelfth Night, and composed a few couplets to introduce each one. Learning her parts kept Tory too busy to fret. Alphonse materialized again to help Jack, Captain Billy and Cully wrestle the planks down from the wagon; it took them only an hour or two to get the contraption set up and functional. After the wagons were sorted out, and the horses seen to, and the pallets put out to air, and the kindling collected for the cook-fire, and after Marcus showed Jack and Alphonse all the new tricks he had perfected, they all sat down to a meal together to drink a toast to a fortunate season at the Bath Hotel.

"They’re holding some sort of fandango Saturday night at the Court House in Charlestown," Jack announced to Tory a few days later, returning from an errand in town. "Some rich merchant is the host, and planters from all round the island are invited."

"And me without a stitch to wear," Tory observed.

"I don’t mean we ought to go, but we should give our first performance that evening, here on our own stage."

"Why, if everyone’s off to the ball?"

"The planters and their ladies and families will be off to the ball," Jack elaborated. "It’s the first of the season, so everyone will attend. Which leaves a great many coachmen, slaves and servants milling about the neighborhood for many idle hours, not to speak of the common folk sure to be out in force to catch a glimpse of the ton in their glory."

"So we’re to give one of our low performances?" Tory teased.

"Well, we might as well have fun and get in some practice before the hotel guests arrive. After that, we’ll be obliged to rattle off verse and socialize for the rest of the season. It would be a shame to miss this chance to make a little something extra on our own account. Cybele can set up a stall with her cards. It’ll be festive, like a fair."

"But how are we to lure them here if everyone’s down the road, outside the ball?"

"We must get their attention," Jack declared. "We must have bills." He pulled a crumpled scrap of paper out of his shirt, unfolded it and handed it to her. On it, he had scribbled the text of a playbill,

Public Performance. Juggling, Comedy and Recitations. Sentimental Songs and Lively Dancing. Featuring the extraordinary antics of Mr. Punch. In the Park Land, north of the Thermal Springs, Main Street, Charlestown. Saturday evening, dusk. Public Invited.

Tory glanced up from the paper. "Is it wise to mention Punch?" They had not dared to play the Harlequinade in the streets of Charlestown last year, after their altercation on St. Kitts, saving the pantomime for Christmas at the hotel.

"But Alphonse has been performing as Punch on this island for years," Jack replied. "He has quite a following. He’s our biggest draw. And I doubt if we’ve anything left to fear from our chief constable back on Basseterre. For all he knows, he’s sold you to smugglers and I’ve died of grief."

Tory handed back the paper. "Then I suppose this will do."

"Good," Jack beamed. "I called in at the printer’s on the way back from town. I would have consulted with you and Alphonse first, but with so few days until Saturday, I chanced I would have your approval. And who knows when we’ll see Alphonse again?"

Indeed, Saturday morning found Jack hot and fuming inside Billy Bruce’s grey tailcoat. He had thought to look respectable when calling at the printer’s for the new bills announcing tonight’s performance, so the printer might give a good account of him, if pressed. But now it seemed a lot of bother for nothing. Alphonse had failed to meet them in the square this morning to promote the event, as planned, and had sent no word. If he failed to turn up tonight there would not be much of a performance, bills or no bills.

Tory and Marcus had danced off anyway, to post the bills as if nothing were amiss. Jack had lingered behind, in case Alphonse appeared, promising to meet them later at the wagon. But now Jack was furious. If Alphonse had wearied of their partnership, he ought to say so, not play these foolish disappearing pranks. That it was so unlike him to miss an appointment only proved to Jack how preoccupied Alphonse had become with his private affairs.

On top of everything else, it was most damnably hot; the trades had been slacking off since sunup. Jack tugged at the brim of Captain Billy’s topper, and cast about in mid-stride for more suitable shade. The blinding white wall of the Court House loomed up just ahead, and turning away from it, Jack spied a cool, covered breezeway down a side street. He struck off in that direction for an arched doorway, through which wafted the muted clattering of pottery and glass, and the low murmuring of a public house, and he ducked gratefully inside.

It was not the sort of groggery he was accustomed to; the furnishings were mahogany, the chairs padded, the ceiling high and the upper walls perforated with windows, to catch every breeze. The custom were white, well-dressed gentlemen in pursuit of their midmorning fortification. Jack thought it might be a private club, but he had come this far, and no one seemed disposed to accost him, not the way he was dressed.

He settled into a shadowy corner, and ordered rum and lime from the potboy, hoping to burn off the heat of his anger. He tossed off a long draught, and stared into his drink, willing himself to calm down. No little part of his anger was due to Alphonse’s failure to confide in him, after all they had been through. Jack had dragged Tory back from the brink of her freedom on the sea to fulfill what he considered his obligation to Alphonse and his work, and now Alphonse treated him in this cavalier manner, as if Jack were some intrusive buckra who could not be trusted. If he failed to appear tonight...

"Tonight!" a low voice snorted, so nearby that Jack jumped; he was more wound up than he thought. "Damned waste of time to wait until tonight, when we know there holed up there somewhere at this very moment, plotting against us!" the voice blustered on.

"By law, we must catch them in the act," came a hushed, reasonable reply. "You can’t hang 'em on suspicion any more."

Jack had them picked out now, three gentlemen planters or their agents with the burned, ruddy complexions of those who had spent all their lives in the West Indian sun. They huddled together round their Madeira at the next table but one, and Jack wondered if he ought to move off. He had troubles enough of his own without soaking up theirs.

"Time was when a man had the right to discipline his own niggers," harrumphed the first speaker. "The law had nothing to say about it."

"Aye, but that was before the abolitionists and the missionaries began spreading their rubbish, giving the darkies ideas," replied the reasonable voice. "But there’ll be discipline enough tonight, once we catch their leaders, depend upon it."

"But why wait? Must all of Gingerland burn to the ground before the law allows..."

"There will be no burning," the reasonable voice insisted. "These fellows are too cowardly to act in the daylight, and in any case, the militia is already standing by. We have only to pack the ladies off to the Court House this evening, out of harm’s way, then we’ll double back and surprise 'em before they can get up to any mischief. We’ll have their ringleaders right where we want them in the middle of things. Nothing will go awry."

"If our information is correct."

"Venus is a good girl, she would never fabricate such a tale," came a third voice, more melancholy than the other two. "I only wish there were some other way."

"Devil the man!" barked the blusterer. "We’ve been through all this before!"

"And yet, I can scarcely credit it," the melancholy voice sighed on. "My most trusted mulatto, raised in the house since he was a boy. Why, Paris is like my own son."

Jack’s blood turned to ice. Alphonse’s small black hand on a tense brown arm. It is all right, Paris.

"Oh, aye, they’re all good sons, until they get a notion to torch your house and fields, rape your women, and murder you in your bed," scoffed the blusterer. "Blood will tell, that’s what I say, and a savage is a savage for all his fine livery."

"We don’t know it’s a rising," the reasonable voice pointed out. "The wench only said there’d been meetings."

"As if that weren’t damning enough. Whatever we find 'em up to tonight, it’ll be enough to identify the troublemakers and send 'em to the gallows. Then we may all rest more easily."

"Have a care how you speak of my property, gentlemen," sighed the melancholy voice. "Slaves are expensive."

"Not to worry," chuckled the blusterer. "We’ll be sure to leave you a buck and a doe for your experiments."

"It is only your slaves that we know about," chimed in the other. "We must wait until tonight to see who else we turn up."

"I know who I’d like to find with his hand in the jam pot," declared the blusterer. "That confounded little darky."

"Which one?"

"Oh, you know, that buskering fellow with the jumped-up Frenchy name. That black dwarf who comes round every year to agitate the niggers. We can’t take the wench’s word alone, but if we were to discover him in amongst the plotters, what a prize he’d make for the hangman."

Jack sat very still, his face without expression, and signaled for another drink. He sat back, nodded to the boy, and took one slow, careless sip, and then another, like any other preoccupied gentleman of business, while the blood thundered in his ears and his stomach dropped away to somewhere deep within the core of the earth. It was no good now cursing Alphonse’s dangerous games, or wondering how they had come to this pass. He must think fast and flawlessly. There could be no miscalculation in his plan; he would get no second chance. He’d be damned fortunate to get a first.

After downing a final toast to their successful enterprise, the gentleman planters departed. Jack took his time settling his bill, and ambled out into the fierce, mocking sunlight a few minutes later. He strolled into the Main Street and up the rise out of town before dodging into the protection of the tree-lined brush and breaking into a run.

Knee-deep in costumes and last-minute plans, Tory nearly jumped out of her skin when Jack thundered up the step into the wagon, and slammed the door behind him.

"God Almighty, Jack, you look as if the hounds of hell—"

"Rusty, listen, there’s not much time," he panted, tossing Captain Billy’s topper on the bed and shrugging out of the tailcoat. His damp shirt clung to him like sagging flesh, as he tore at his stock. "There’s a slave rebellion planned at some outlying plantation tonight, when everyone’s here at the ball. But it’s a trap, the planters know all about it, I overheard them in a tavern. They’re planning an ambush."

"But what—?"

"Alphonse is involved." Jack seized his old plantation linens off a shelf, and pulled them on. "Don't ask me why or how. That fellow Paris is one of the leaders."

"Alphonse would never take part in a rising!"

"It may not be a rising, but the planters think it is. The militia is standing by." He finished dressing, and rooted out his battered straw hat.

"But it doesn’t make any sense! Why would Alphonse—?"

"I don't know why," Jack grimaced. "It doesn’t matter why. Anyone they take tonight will be hanged."

Tory swallowed her next protest. "What are we going to do?"

"You are going to stay here," said Jack. "I’m going to warn them."

"What!"

Jack turned away toward the water jug.

"How do you know where they are?" Tory demanded.

"Gingerland," Jack muttered, pouring water into the basin.

"That's an entire district! You’ll never find—"

"I described the planter to Marcus. He’ll turn up some carter or stable hand who knows which estate is his. I’ll find them."

"And then what?" Tory could scarcely think through her own hot, rising panic, but she remembered all too vividly the cold hatred in Paris’ eyes. "You’re a white Englishman, and a stranger. If they are plotting a rising...they’ll kill you, Jack."

"Not if Alphonse is with them."

"But what if he’s not?"

"But what if he is?" Jack straightened up from the basin; his eyes were desperate. "I can’t let him walk into a trap if I can stop it." He seized a towel, and rubbed it over his face.

"But...you promised me," Tory pleaded.

"Hellfire, Rusty, what else can I do?"

"Let me go," she urged him. "They’ll take me for mulatta."

"Oh aye, I’m to sit idly by while you’re off getting yourself raped and murdered on some lonely mountain road—"

"That’s what you expect me to do!" Tory cried.

"I expect you to stay here and put on a performance."

She stared at him as if she had never before heard the word.

"No one is supposed to know anything about this rising, or the ambush," Jack pressed on, flinging the towel away. "It would look odd if we canceled our performance with all the bills posted, especially for Alphonse. They suspect he’s involved, but they must catch him with the conspirators to make their accusations stick."

"But...he won’t be here," Tory protested. "You won’t be here."

"We might. It’s some hours yet to nightfall. Rusty, please," he went on quickly. "Who else can I trust?"

Tory bit back her foolish whining. "What do you want me to do?"

"You must stage-manage some sort of show, tonight. You have the Bruces and Marcus. Cybele and her stall. You must all work around us somehow until we get back." He plucked up his straw hat, and stuck his knife in his waistband. "The point is, whatever you set up must look like the performance we planned from the start. It mustn’t look as if anything at all is amiss."

Tory nodded slowly, as they stood where they were, eyes locked across the room, separated by the vast expanse of words there was no time to say. Then the door swung open and Marcus tumbled in.

"You be in luck, Jack, evahbody know that fellow!" And in pleased, breathless bursts, the boy described the landmarks that would lead Jack to the estate, and whatever fate awaited him there.

"Well done," Jack beamed at him. "I knew I could depend on you."

"What you got to go there for?" Marcus asked.

"There’s someone there to whom I owe a great debt of honor. It must be paid today."

"But what about tonight?" Marcus’ face clouded a little.

"A man must pay his debts," Jack shrugged, feigning lightness. "You may have to fill in a little onstage until I get back. If you’re up to it."

Marcus broke into a grin. "Me do anyting you want. You see!"

"Good. Do whatever Tory asks. We’ll see what you’ve learned."

The boy scampered off and Jack pulled the door to behind him, and faced Tory again.

"I’m taking Shadow, he knows these back roads." The strain of maintaining his nonchalance for Marcus’ sake now showed plainly in Jack’s eyes as they searched her face. "I don’t have to tell you that this conversation never took place."

Tory nodded, afraid to open her mouth for all the fear that would come pouring out.

"Stand by tonight, in case we have to leave suddenly. Don’t answer any questions. If there’s no word by morning—"

"Jack—"

"Stay with the Bruces. Return to English Harbour, it will be safer there. Don’t," he whispered, when she opened her mouth again. "There’s no time."

And he was gone.

Tory stood as if bolted to the floor, staring at the doorway where Jack had been. She had not kissed him, had not even touched him. She hadn’t said goodbye. Then mobility returned and she sprang to the door and flung it all the way outward, just in time to see Jack righting himself on Shadow’s broad back, tugging his bridle toward the road. They trotted through the palms, opened into a full gallop and disappeared up the slope toward the Bath Hotel and the high road behind it, leaving only an echo of percussive hoofbeats behind. Tory’s heart pounded in response, as if it would burst her ribs apart. She couldn’t breathe, couldn’t think. She clutched at the door frame for support, and stared into the empty road. The one thought pounding in her head escaped her lips in a fierce whisper.

"Come back to me, Jack."

(Top: Harlequin On Horseback, German school, 19th C, as seen on www.elite-view.com/)